Immunotherapy is a promising cancer treatment that uses genetically modified immune cells to fight cancer.

The immune cells used in the therapy can be used as a primary treatment, or in combination with other treatments such as radiation and chemotherapy, to slow down or stop the growth of cancer cells and prevent them from spreading to other parts of the body.

Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy, for instance, is a FDA-approved treatment for some cancers such as lymphoma and leukaemia. It involves collecting T cells (a type of immune cell) from a patient’s blood sample and then genetically modifying them in the laboratory and infusing these immune cells back into the patient. The genetically engineered immune cells will then locate and kill cancer cells.

However, the process known as transfection to generate genetically engineered immune cells in the laboratory has poor efficiency and may have serious side effects. Scientists around the world are therefore looking for strategies to improve the overall efficiency and to reduce the side effects of cancer immunotherapy.

Dr Andy Tay, a researcher with the National University of Singapore (NUS) who is currently doing his post-doctoral training at Stanford University, has successfully invented a novel transfection method to deliver DNA into immune cells with minimal stress on these cells.

Dr Tay, who is with the Department of Biomedical Engineering of NUS Faculty of Engineering said: “We feel anxious when we experience a late and inefficient courier delivery. Similarly, the cells in our body get ‘uncomfortable’ when DNA is not delivered to them effectively. This is especially true for sensitive immune cells which have to begenetically engineered with DNA to transform into super-soldiers for cancer immunotherapy.

“When immune cells do not function properly, they may trigger undesirable medical complications too.”

This new technique, which was reported in scientific journal, Advanced Therapeutics, on 30 September 2019, is expected to boost DNA-based cancer immunotherapy by significantly improving the process of generating high-quality genetically modified immune cells.

Carrying DNA efficiently into immune cells

Viruses, biochemicals and bulk electroporation (where an electric field is applied to cells to make the cell membrane more permeable, so that chemicals, drugs, or DNA could be introduced into the cell) are the conventional methods to deliver DNA into immune cells. However, these methods are inefficient and have recently been shown to induce high cell stress, hence compromising the effectiveness of immunotherapy.

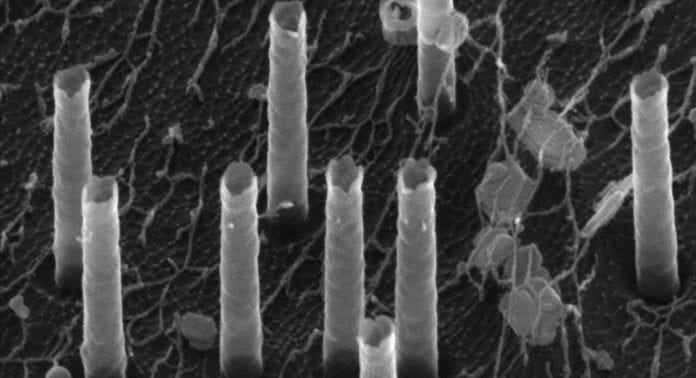

The technique developed by Dr Tay, called nano-electro-injection, works by applying localised electric fields through nanotubes (about 5,000 times smaller than a grain of rice) to open small pores on cell membrane. As DNA is charged, they are drawn by electrical forces into cells through the pores.

Compared to viruses, biochemicals and bulk electroporation, the nano-electro-injection technique delivers DNA material to cells two to three times more efficiently, and this is based on the gene expressions that the DNA is supposed to code for.

Additionally, cells treated with nano-electro-injection grew healthily like control untreated cells, unlike other methods where cells took 20 to 40% longer time to multiply. This is good news for immunotherapy as a large number of cells are needed for treatments, and growing cells is one of the most time consuming and expensive steps.

Making use of RNA and bioinformatics analyses, Dr Tay also discovered that unlike bulk electroporation, nano-electro-injection treatment did not significantly change the expressions of any immune genes. This is a strong advantage as toxic immune responses such as cytokine release syndrome can be deadly and until now, the effects of transfection on the expressions of immune genes are unknown.

Professor Nicholas Melosh, an expert in materials science and engineering at Stanford University who supervised Dr Tay’s research, said: “This work found new alternatives for a critical step within the pipeline for expensive new cancer therapies. Dr Tay’s work also highlighted how different processing steps can affect not only the efficiency of the process, but overall cell health, and thus increasing the likelihood the cells will perform as desired after treatment.”