Dave Crucefix explores the history of whole-body vibration therapy, culminating in advanced Low-intensity Vibration (LiV) and the Marodyne LiV device.

From the ancient Greeks to the present day, NASA scientists and physicians alike have been fascinated by the beneficial effect of whole-body vibration therapy.

Methods to speed healing and strengthen those recovering from injuries have been a target of medicine throughout the centuries. The ancient Greeks discovered activity and vibrations aided recovery from injury; special carts with irregular wheels aimed to speed healing were mentioned by Lucius Annaeus Seneca in his writings.1 These were often run over uneven ground to increase the level of vibration and speed up the healing process.

A 16th-century Japanese book describes the potential benefits of vibrations for health, with particular emphasis on using vibration therapy to help mend fractured bones and aid rheumatic conditions.2

Similarly, the ‘trémoussoir’ or ‘fauteuil de poste’ was invented in the 18th century by Charles Irénée Castel de Saint-Pierre (better known as ‘Abbé de Saint-Pierre’ (1658-1743).3 Used to help the infirm improve their nervous system, he even convinced the highly sceptical François Marie Arouet, better known as Voltaire, of its efficacy.

Early innovation

Fast forward to the 19th century and major medical and technological advances enabled further uses of vibration therapy.

Jean-Martin Charcot, a notable identifier of neurological diseases, designed a vibratory chair. He used this chair to treat his patients with Parkinson’s disease and noted, ‘Once the patient steps out of the vibratory chair, he feels lighter, rigidity disappears, and walking is easier.’4

Charcot also designed a vibratory helmet to aid in the relief of patients’ migraines and other neurasthenics. Charcot concluded, ‘there can be little doubt, further to what I have said here, that vibration used in this way is a powerful sedative for the nervous system’.5

Swedish doctor Jonas Gustav Zander established much of what we know as the modern gym. With the ‘Zanderapparat F2’, Zander simulated the jog-trot type experience of riding a horse. In 1895, Dr John Kellogg of the American Sanitarium (and cornflakes breakfast cereal) improved upon Zander’s design. Kellogg invented vibrating chairs, bars, and platforms and used them in his Battle Creek Sanitarium for therapeutic measures. The first generation were steam-powered and could deliver whole-body vibration therapy to up to five individuals.6

Interest in the use of vibrations in medicine declined in the 20th century until the 1960s when Professor Biermann developed the Rhythmischeneuromuskulare Stimulation (RNS). This was developed further by Vladimir Nazarov and used by the athletes in the 1970s Russian Olympic team.7

One giant leap for bone health

Whilst weightless in space, astronauts lose an average of 1-2% of their bone mineral density per month.8 This poses a significant challenge to astronauts spending prolonged periods of time in space – such as on the International Space Station (ISS) or future missions to Mars.

Recognising this problem, NASA tasked biomedical scientist, Professor Clinton Rubin, with leading the NASA vibe project. Professor Rubin and his team of researchers investigated the potential of vibration therapy and developed Low-intensity Vibration (LiV) therapy as a solution. By using gentle, targeted vibrations, LiV therapy stimulates the mesenchymal stem cells in the bone to reproduce.

Professor Rubin and his team quickly realised the potential the technology had to combat osteoporosis on Earth. Through years of testing and development, Professor Rubin and his team developed a fully functional, safe, and effective vibration platform: the Marodyne LiV device.

How does the Marodyne LiV device work?

In-depth research has been done on exercise and its impact on the body. When we exercise, we increase muscle, expand our lungs, and strengthen our hearts, leading to better health.

But what about our bones? Exercise will strengthen bones and improve bone density. For example, a professional tennis player may have 20% more bone density in their playing arm.9

The body is a smart, auto-repairing system that senses increased use and improves bone density to support the new levels of stress. This can be seen in people from all walks of life.

People with heavy physical work roles are typically larger and stronger than those in more sedate roles. Whereas astronauts in a near zero-gravity environment have very little resistance to work against. This leads to muscle wastage and a reduction in bone mass. Bone mass decreases as the limbs need to support less weight and the body automatically adapts. Great in space, not so good when you return to Earth and its gravity!

As we understand these processes, we can deploy tools that mimic the activity and encourage the body to respond and build bone density. During exercise, muscles contract and pull bones, and the body responds by strengthening the bones and the muscle. Muscles do not always act smoothly and consistently, however.

In most muscle groups, individual muscles do not provide a sustained pull. They only apply a quick ‘twitch’. The constant pull is created by the brain activating groups of muscle cells within a muscle in a rapid, repeating pattern. This can be felt by squatting and resting your hands on your thighs and feeling a very small trembling of the muscles. The frequency of these can range from 10-100 cycles per second.10 These trembling twitches are understood to provide stimulation to the bones and trigger the generation of bone mass.

Most treatments for osteoporosis use several drugs, supplements, and vitamins to maintain or build bone density. The Marodyne LiV device uses low-intensity vibrations that mimic the natural mechanical signals that trigger our bones to regenerate.11

The frequency of the Marodyne LiV device is calibrated to 0.4g at 30hz – the precise calibration Professor Rubin found to safely stimulate osteoblast (bone-building) activity and inhibit osteoclast (bone-wasting) activity.

Studies have established that standing on the Marodyne LiV device for just 10 minutes a day can help prevent and combat osteoporosis, providing a drug-free way to naturally improve bone health at home, with no contraindications.

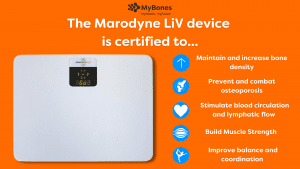

In addition, Marodyne LiV is certified as a class IIa medical device by the British Standards Institute (BSI), and has been scientifically proven to:

- Prevent and combat osteoporosis;

- Increase bone mineral density;

- Build muscle strength and mass;

- Stimulate blood circulation and lymphatic flow; and

- Improve balance and coordination – reducing falls.

References

- Kaeding TS. ‘The Historical Evolution of the Therapeutic Application of Whole Body Vibrations: Any Lessons to be Learned?’. Austin Sports Med. 2016; 1(1): 1003

- Snow, M. L. H. Arnold. ‘Mechanical Vibration And Its Therapeutic Application’. New York: Scientific Authors’ Pub. Co., 1904

- Kaeding TS. ‘The Historical Evolution of the Therapeutic Application of Whole Body Vibrations: Any Lessons to be Learned?’. Austin Sports Med. 2016; 1(1): 1003

- Goetz CG. ‘Jean-Martin Charcot and his vibratory chair for Parkinson’s disease’. Neurology. 2009;73(6):475-478. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b1640b

- Walusinski O: ‘Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893): A Treatment Approach Gone Astray?’ Eur Neurol 2017;78:296-306. doi: 10.1159/000481940

- Ruscoe, Glenn. ‘Vibrator’. History.Physio, 9 Apr. 2021, history.physio/vibrator/

- Kaeding TS. ‘The Historical Evolution of the Therapeutic Application of Whole Body Vibrations: Any Lessons to be Learned?’. Austin Sports Med. 2016; 1(1): 1003

- Stavnichuk, M., Mikolajewicz, N., Corlett, T. et al. ‘A systematic review and meta-analysis of bone loss in space travelers’. npj Microgravity 6, 13 (2020) doi.org/10.1038/s41526-020-0103-2

- Calbet, J A et al. ‘Bone mineral content and density in professional tennis players’. Calcified tissue international vol. 62,6 (1998): 491-6. doi:10.1007/s002239900467

- ‘Good Vibrations’. Nasa Science, 2 November. 2001, science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2001/ast02nov_1

- Pagnotti GM, Styner M, Uzer G, et al. ‘Combating osteoporosis and obesity with exercise: leveraging cell mechanosensitivity’. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(6):339-355. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0170-1

This article is from issue 21 of Health Europa Quarterly. Click here to get your free subscription today.