Katrina Delargy, of TIYGA Health, explains how app-based data collection can enhance research and public awareness surrounding COVID-19.

The past year has seen unprecedented changes in how many aspects of life and work are conducted; our perspectives on life as we knew it had to change dramatically. COVID-19 has affected every aspect of life – work, health, education, leisure, family, and relationships like never before. Subsequently, our public health response and approach to data collection had to become smarter. Over the past 18 months, our understanding has evolved:

- The signs and symptoms of COVID-19 were initially predominantly associated with breathing difficulties and a continuous or new cough;

- Early in 2020, the public health messaging distinguished COVID-19 from the common cold; we were advised that a runny nose was not a sign of the virus;

- By summer 2020 (following analysis of ZOE app data) loss of smell and taste were added to the NHS list of three core symptoms but we were concerned about asymptomatic transmission;

- Later in 2020 and during 2021, the focus shifted to the transmissibility of new mutations; and

- In summer 2021, many patients reported a sore throat and runny nose, the original core symptoms (e.g., continuous, or new cough) are less often named in the top five symptoms.

While in winter, distinguishing COVID-19 from the common cold and flu are important, in summer the comparison with the signs and symptoms of asthma and hay fever are more relevant.

Increasingly, we worry about the possibility of mutations that could escape our vaccines. Viruses evolve to get smarter, so we must evolve our approach to fighting them and, thankfully, our scientists are successfully updating the vaccines. COVID-19 has sharpened our focus on daily data from individuals.

Fighting a virus – outwitting the invisible enemy

Valuable data has been obtained from epidemiological studies using app-based real time reporting. The app was launched by health science company ZOE with scientific analysis provided by King’s College London. With over four million contributors globally, it is the world’s largest ongoing study of COVID-19. People around the UK contribute data on their symptoms but also on their vaccinations, diet, and aspects of mental and physical health.

Interestingly, the app also gives links to a wide range of articles and short videos that help to inform and educate citizens about how the research is progressing, what is being learned from data submitted by participants in their local area and ways in which they can protect and improve their own health. While the initial app was focused on making daily data entry easy, the researchers are also providing relevant information to them in real time. This is more than research; it is patient and citizen engagement. It is scientifically directed but also actively engaging with the beneficiaries. The app data is interpreted for clues about the characteristics of a virus-induced headache or allergic reaction, it is giving people a convenient and relevant insight into the impact of the virus. People can also seek advice on symptom control from a pharmacy, where it is easy to walk in and ask. Getting appointments with GPs is not always easy – and with COVID-19 it is vital to act quickly. Timing is crucial.

The speed of development and rollout of vaccines has been a truly remarkable success. Imagine if the vaccine development had proceeded at the same rate as previous vaccines (10 to 15 years) – what would the statistics for deaths have been by now? All aspects of research, development and delivery were accelerated to achieve the goal. If the ‘enemy’ is nimble and spreads fast then the means to combat it must be equally speedy and at least as smart.

COVID-19 has been a unifying factor in many ways, we fear and wish to control it and end the grip it has on our way of life. Most people understand that we have been in this together, many people are willing to contribute their knowledge and observations for the common good (and self-interest) and through a desire to win the war on the virus. For those who did not live through a world war, this is perhaps the closest experience they have had to facing a widespread life-threatening risk. Citizens want to support scientists and most play their part. So, should this crucial public involvement end with COVID-19? Could it be part of how we develop healthcare solutions more broadly? Certainly, the public awareness of scientists and their specialities has dramatically increased, and the best communicators have found a new role in the media as the public hunger for data and explanations has grown during the pandemic.

The next challenge is to extend the learning from the public response to app-based epidemiological research. We need to build on the increased public awareness of health issues by expanding the opportunity for research on app-based data entry for primary and secondary care. Consumers are embracing the convenience and personalisation of digital data collection and may reject traditional paper-based methods; questionnaires are often not returned and therefore not a comparable reliable data source. People value their time, they respond when the data capture is relevant, timely and easy. This can effectively start in targeted use cases where the benefit of patient-generated-health-data (PGHD) is going to make a real difference to health outcomes, timely interventions, and resource efficiency.

Impact of clinical research – weapons for viral destruction?

Pre-COVID clinical research was, arguably, conventional, and rather formulaic in the race for publications. The COVID crisis has sharpened the focus and new ways of doing good research have been emerging. There were extensive criteria for inclusion and exclusion, the methods were rigorously chosen to reflect a deep and mature knowledge base. The more something was used, the more likely it was considered to be reliable as a validated research instrument. But does it not also follow that some of the long-established tools might not be optimised for the research we now need to do?

Relevance is surely a key factor in the success of research, relevance going forward – relevance to the population affected and to their way of life. Research must deliver the promise on which the funding was justified. Good research aims to have generalisable conclusions that are robust and include patient-reported data which will surely become the gold standard in future. Such research aims to improve some aspect of how we live and do our work, building in real world data can add to the richness of the conclusions. With that perspective, surely there is a good scientific basis for real time symptom reporting and research methods that engage those patients who are suffering most with an illness. Consumers can actively report how symptoms manifest themselves in a time sequence as well as a narrative, without recall error. Patient engagement is vital for good outcomes.

Just as we can learn from the epidemiology of COVID-19, we can surely also learn about the development and treatment of other diseases – not just the communicable public health issues but the non-communicable and debilitating illnesses that limit the quality of life of so many. Just as patient involvement is helping with research in long COVID, is there any reason why this should not be the case with cancer, dementia, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, migraine, asthma, irritable bowel disease and many others? Early warning of exacerbations is likely to be possible, even if this cannot always prevent serious incidents. Such research could inform the protocols informing transition between care settings and help emergency departments to be even better prepared for patients as they arrive in distress. We can discover the nuances that traditional questionnaires, designed years ago, might not have sought. The knowledge of lived experience is valuable if we can capture it efficiently.

Real time research – convenient, relevant, and cost-effective

Of course, all research does not have to be real time. However, now we are seeing the value of constantly updating our knowledge of disease spread and management, we must have methodologies that are accepted as valid for those cases where real time data is most valuable.

Long COVID is an example of where patient-led research has and will continue to be the most effective way for patient participation to happen. For long COVID, the population of sufferers is typically 35 to 69 years – most of whom are likely to have a smartphone and some confidence with using digital. Long COVID sufferers are from all walks of life, professional and non-professional, prior to the infection and may now be unable to return to their normal job. Often long COVID patients are highly motivated to browse the web and social media for any research that could improve their condition, many have found their GP did not have much to offer except a series of blood tests and general remedies. Long COVID patients do not rely on prescribed medicines, they embrace a wider range of options to manage their symptoms. These people are not just motivated to participate in research about their condition, but they are informed about emerging thinking on the virus, testing and treatment. These patient-consumers are actively contributing to knowledge of what to investigate and what might be effective. Long COVID, by definition, persists a long time and symptom patterns may change. There are often periods where they think they are getting better but then the symptoms return. The problem does not stand still, boundaries change. The research must be dynamic.

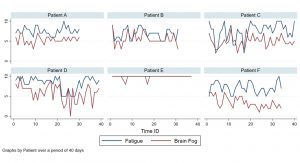

So real-time research must accommodate the realities of what is being studied. Rather than spending months crystallising the protocol, before inviting participants and sending the inclusion-list a lot of paperwork, is there a better way? We all know that research has drop-out rates and we all know that apps have dropout rates too; the statistical planning has to incorporate assumptions on how much data will be captured to achieve valid conclusions. Good science normally demands that people report at controlled intervals, to suit the statistical analysis. Researchers should choose the right tools for the purpose. TIYGA™ is one example of a real time data capture tool that has proven acceptable to patients with long-term conditions and long COVID (Fig.1), whose duration is yet unknown. Perhaps the research design should accommodate the fact that patients may have brain fog and fatigue as well as a great need for sleep? Data capture should not impose unreasonable demands or constraints on the patients and their ability to record meaningful answers in near real time.

Feedback and dissemination normally take place months or years after the data have been captured, and long after the research question was formulated. For the patients who give their time and energy to contributing to research, there is an argument for rapid dissemination of results as soon it is prudent to do so. Translation into practice is important.

However, when we do real time research that involves lived daily (or hourly) experience being reported by those motivated to find a cure quickly, are we doing them an injustice by planning the way we did pre-2020? Chronobiology is helping us to understand daily patterns, especially relating to eating and sleeping. Real time data about daily routines could support adoption of healthier lifestyle choices.

Learning from patients – engaging patients in real time research

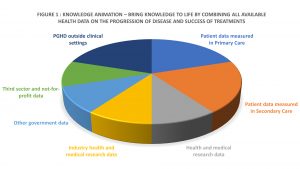

All research should be cost-effective, so app-based submission of data should be included to minimise expenditure. We need to combine the knowledge of lived experience via PGHD (Fig. 2), with the knowledge acquired over many years, by many people in many ways. We should also take account of real-world changes in the illness, experience of it and the impact it has on quality of life. Without the detailed data about what happens outside clinical settings, how can we predict, prevent, or pre-empt exacerbations and incidents through intervention at the right time and place?

Bringing knowledge to life (knowledge animation™) that was previously thought not important into structures and frameworks, makes that knowledge amenable to machine learning and enables us to obtain richer insights that benefit us all.

Katrina Delargy

Managing Director

TIYGA Health

www.tiygahealth.eu

This article is from issue 18 of Health Europa. Click here to get your free subscription today.