Chris Allen, Executive Director of Hemp Federation Ireland, tells MCN about the Irish hemp industry.

Founded at the Humanities Institute, University College Dublin (UCD) in January 2019, Hemp Federation Ireland (HFI) is the national representative body for the Irish hemp industry. Membership spans the cannabis industry value chain, including the largest employer in the sector and Ireland’s oldest and most prestigious hemp companies.

How did Hemp Federation Ireland come to be founded?

HFI was founded following publication of the influential Hemp Report. The report was originally submitted to members of Ireland’s Oireachtas (parliament) in response to evidence presented by a delegation from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), headed by Professor Valerie Masson-Delmotte. It outlined the potentials of the Irish industry in the context of global market expansion and called for a strategic plan to maximise integrated benefits across economic, health, agricultural and environmental policy contexts. Prior to the release of the Hemp Report, there had been no research on hemp in Ireland for almost two decades and its publication sparked intensive activity in the sector.

Bord na Mona – Ireland’s state agency with responsibility for peatland bogs – moved quickly to declare its interest in hemp and cannabis markets. Later in 2019, Ireland’s youth assembly recommended the development of the Irish hemp industry. Ireland’s 2020 Programme for Government now includes a plan to establish a fibre-only industry; this would see the food value of the crop transferred from the hands of farmers to Ireland’s huge cohort of (mostly American-owned) pharmaceutical interests.

What is HFI’s role within Ireland’s hemp industry?

The expertise of HFI’s internal advisory panel is supported by the organisation’s internal research capacity: this ensures strong, responsive, and consistent leadership in an increasingly complex policy and trade environment. HFI promotes a fully integrated, farm-based development of the industry; and we represent the views and common interests of our members across government departments and agencies. Although Ireland is home to some of Europe’s foremost industry authorities, the state continues to regulate without stakeholder involvement. Therefore, HFI provides extensive regulatory support to ensure our members’ products continue to meet the highest international quality standards – establishing appropriate standards within the domestic market is crucial to protecting Ireland’s external markets into the future.

More broadly, HFI argues for fully integrated farming and industrial practice across combined cannabis sectors – including pharmaceutical and recreational cannabis production. We strongly contend that it makes little economic sense for the industry, and none whatsoever for governments, to persist in ‘doing the wrong thing wronger’ when there is an unprecedented opportunity to put this extraordinary industry on the right track from the beginning.

What is the current legal status of hemp in Ireland?

It is currently legal to grow hemp in Ireland under licence from the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA). Only crops grown from EU-certified seed and containing below 0.2% THC are permitted. THC is regulated as a controlled substance by law enforcement officials in strict accordance with domestic Misuse of Drugs legislation. No amount of THC is currently permitted for sale in Ireland except under licence from the Minister for Health, who reserves such licences for medicinal cannabis products and related research activities.

What are the agricultural and sustainability benefits of hemp?

Regulation of hemp and cannabis is a threefold interconnected matrix across agrifood policy, climate policy, and the designation and regulation of medicinal products. The 2018 IPCC Report establishes that effective climate transition pathways are all centred on high protein, low energy food production. While the environmental and sustainability potentials of hemp are now more widely understood, the pivotal context of food remains entirely absent from the conversation.

Given the power of the pharmaceutical sector and its global push to control what happens with hemp, it is worrying that so many Departments of Agriculture, including in Ireland, appear to have abandoned farmers in order to permit Departments of Health to regulate agriculture in the interests of pharmaceutical companies. Ignoring all advice from the World Health Organization, governments around the world continue to regulate this agricultural crop as a newly discovered narcotic, thus ensuring its food value remains entirely unrepresented in farm policy, food policy and climate policy debates. The scientifically unsupported problematisation of hemp in political discourse – and the introduction of rules and regulations to then address these ‘problems’ – is at the core of a wider ethical issue in the cannabis policy frame: it centres, not on access to cannabis as medicine, but on access to hemp as food in the context of climate change.

Hemp is the most complete plant-based protein known to man. It provides the same amount of high quality protein as an equal portion of red meat, it contains all essential amino acids plus omegas 3, 6, and 9, and almost every other essential nutrient required to support healthy human growth and development. In addition, cannabinoids and terpenes in hemp interact with the endocannabinoid system to provide a completely unique support for the human body and immune system – it is a plant-based source of human health nutrition that exists in a category of its own.

World soil health reports show that due to human activity and industrial farming, the fertility of the earth’s soils has reduced by around 40% on average since 2008: this means the plants we currently grow to feed ourselves do not yield as much as they once would have. This also means the soil cannot capture and store carbon as it should. As temperatures rise, the food crops we now grow will produce smaller yields and some may not grow at all at higher temperatures. At the same time, the world population is growing rapidly and is set to exceed 10 billion by 2050. This means increasing demand for food will place increasing pressure on already exhausted soils to produce more food with less capacity in increasingly hostile conditions.

Field-grown hemp requires little water or energy resources and needs no pesticides or other agricultural chemicals to thrive. It naturally outcompetes weeds and grows well in most climates and on marginal lands. It is one of the most prolific bioremediation agents known to man, which means it vigorously removes toxins and chemicals from the soil. In cleaning the soil, hemp also restores soil fertility, so when grown as a break crop, it will increase the yield of follow-on crops by upwards of 30%.

Is Irish regulation and policy on hemp fit for purpose?

The global pharmaceutical lobby spends about €40m annually in Europe and EU pharma interests are heavily concentrated in Ireland. In recent research from Poland, Jacek Kramarz demonstrates a link between changes to the EU Novel Food catalogue and increasingly stringent domestic enforcement practices across EU Member States – the same research shows Ireland’s regulators have been particularly aggressive. Certainly enforcement practices are increasingly extreme and chaotic in Ireland; and they disproportionately impact Irish-owned businesses, leaving other market actors relatively unscathed. Thus, the internal market has largely remained open while Irish businesses and farms are systematically devastated.

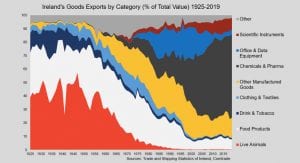

The graph above correlates the growth of the pharmaceutical sector in Ireland with the demise of domestic Irish industries. What it says about Ireland’s farming sector is particularly poignant in light of growing policy discussion around synthetic meat and future investment in synthetic vegetable-food production; these discussions position lab-grown food as a way of tackling climate change. The policy argument is that if you disconnect food production from land use, you can rewild landscapes and almost entirely remove climate-associated risks to primary food production. From this point of view, the interventions of Irish regulators, government officials, state departments, and enforcement bodies in deconstructing not only the Irish hemp industry, but the hemp plant itself, are highly provocative.

February 2020 saw truly regressive measures shoehorned into place via the Food Safety Authority of Ireland’s (FSAI) Market Survey Report. Prior to its publication, official FSAI advice to industry was that products containing below 0.2% THC could be sold in Ireland, ‘including for food’ – the FSAI now denies that this regulation ever existed and all reference to it was removed from the FSAI website immediately prior to the report’s release, despite the fact that the purpose of a Market Survey in principle is to measure compliance with known standards and FSAI didn’t mention they had changed the regulations inside of their report. The FSAI then removed compliant products from the market in the context of a national media campaign to inform people of the dangers of those products. The national broadcaster refused to grant the industry a right of reply, citing the FSAI’s status as a competent authority.

The FSAI report has had far-reaching consequences for the industry in Ireland and is now routinely referenced to legitimise bizarre activities across state agencies, which includes armed Gardai raiding the homes of Irish consumers who buy farmed hemp products. Hemp Federation Ireland has called repeatedly for the withdrawal of the FSAI report and for an independent enquiry into the manner of its production and publication.

Has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted hemp producers in Ireland and have they been able to access economic support?

Publication of the FSAI report resulted in the cancellation of seed orders by Irish farmers and significantly reduced Ireland’s 2020 acreage under hemp. The Irish small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) sector as a whole suffered an estimated revenue shortfall of between €6bn and €10bn between March and June 2020. While the Irish government rolled out a suite of enterprise support, the FSAI report was used to exclude all hemp businesses – including those engaged in fibre-only markets – and only pharmaceutical companies operating in the sector were eligible to apply. Interestingly in this context, the decision to suspend plant-based Novel Food applications in Europe was quickly followed by the launch of Ireland’s first synthetic CBD food products from the pharmaceutical sector.

Should hemp be regulated under Novel Foods legislation?

The upcoming decision on the Kanavape case from the CJEU will hopefully clarify many of the issues with regulation of the European hemp industry. Hemp is not a Novel Food and should not be regulated as such, in the EU or anywhere else. Whole plant extracts obtained through extraction processes listed in Annex 1 of Directive 2009/32/EC are also not novel. Isolated and synthetic cannabinoids, and products with a cannabinoid content above what is naturally present in the plant, are Novel Foods.

Chris Allen

Executive Director

Hemp Federation Ireland

www.hempfederationireland.org

This article is for issue 4 of Medical Cannabis Network. Click here to get your free subscription today.