Australian medical cannabis pioneers, LeafCann, provide a detailed analysis of the effects of THC, examining the potential risks imposed by the cannabis compound.

In this article, LeafCann looks at why a thorough evidence-based approach to THC as an ingredient in medicines and consumer goods is needed to assist our understanding of responses to different dose forms, risks, and safety profiles, providing regulators and physicians with the necessary information they need to have confidence prescribing THC containing medicinal cannabis and CBPM products. Furthermore, producers and consumers of CBD novel food products need certainty about the thresholds and effects of controlled cannabinoids in products widely available throughout the United Kingdom.

THC is well characterised as the main psychoactive molecule within cannabis and historically could not be studied extensively due to regulatory limitations of the global prohibition associated with the ‘war on drugs’. As a result, the evidence base lagged behind access in some jurisdictions where approval has been given for its use in medicine or low doses within consumer products. Now researchers have the ability to study it more acutely; it is time to resolve some long-lasting questions about the effects of THC.

Why do we need more evidence?

Many will argue that much evidence shows THC has a safe history of use and has enough certainty to be prescribed in doses that provide a therapeutic effect. However, in many jurisdictions, the approach to regulating THC is driven by an entrenched view that there is not enough evidence to approve its widespread consumption, even at microdoses. So, the question is, what is the level of evidence needed by governments and the medical profession to be reassured about the safety and efficacy of THC?

The cannabis industry has experienced the legacy of negative perceptions driven by the ‘war on drugs’, that has no basis in science. However, this is not the entire reason THC has experienced so many roadblocks in the bid to use it in medicine and consumer products.

Evidence regarding THC safety

Safety is the first area of concern for governments around the world. Long before considerations about whether THC can be effectively used in some conditions or diseases, the possibility of the effects of THC being adverse must be addressed.

So how do we prove safety? The pharmaceutical industry and fields such as toxicology have found several ways to demonstrate if a chemical is safe or not. These tests all have one thing in common. That is, they are focussed on establishing a level of certainty as to whether a certain chemical or interaction of chemicals can be confidently used by humans or not. It is the concept of ‘certainty’ that needs to be established for THC.

The certainty of cannabis

Cannabis is a relatively safe drug, and it is not associated with fatal overdoses. Based on animal lethal dosing studies, the human lethal dose of THC has been extrapolated to be >15,000 mg.1,2 This highlights that THC has a very wide safety margin, as this lethal dose is 750 times greater than a typical intoxicating dose of 20 mg and proves practically impossible to achieve by oral or inhaled administration. Unlike opioids, cannabis does not cause respiratory depression because of a paucity of cannabinoid receptor expression in the brainstem.

Current UK controlled drug legislation limits THC and other controlled cannabinoids to a total of 1 mg per unit within a container in the UK. This is already a very conservative limitation, which has found no adverse effects to date. For example, in Australia, Therapeutic doses of THC (5–20 mg) within prescribed medicinal cannabis under special access programmes tend to be much lower than CBD dose levels (e.g. 50–1500 mg). Many combined products, therefore, contain CBD:THC ratios of 10:1, 20:1 or 50:1, with 250,000 scripts for such combinations having to date been approved.

Given the wide safety margin in terms of a lethal dose, the tests for margin of safety are not necessary. Establishing more certainty for cannabis, and THC specifically, requires the detailed development of cannabis’ margin of exposure (MOE) and further analysis of the dose-response relationship.

Margin of exposure is the ratio of no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) obtained from animal toxicology studies to the predicted, or estimated, human exposure level or dose. It is commonly used in human health risk assessment (i.e., assessing the safety of a cosmetic ingredient or a food impurity).

For a chemical substance with health thresholds (i.e., not genotoxic and not carcinogenic), an MOE >= 100 is generally considered to be protective.

- MOE = NOAEL/Estimated Exposure Dose

- Unit of NOAEL: mg/kg bw/day or ppm

Sometimes, a higher MOE than 100 is needed when:

- The NOAEL is not obtained from chronic toxicity studies while exposure is chronic;

- Only a LOAEL (Lowest doseat which there was an observed toxic or adverse effect) but not a NOAEL was identified.

- There are uncertainties regarding the quality of the available data

- There is a probability for underestimation of exposure

- There is a need to protect sensitive groups of people

In general, a MOE >= 10,000 is considered to be protective. Cannabis has a MOE greater than 10,000 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4311234/).

For context, the low rate of cannabis-related deaths has been consistent around the world for some time. Statistics from Australia reveal that while unregulated cannabis use has been widespread, with some 1.4 million Australians believed to use cannabis illicitly within a 12-month period, the death rate remains at 0.1 per 100,000. The addition of some 125,000 medicinal cannabis patients has also not increased this rate.

By contrast, in 2018, opioids were present in nearly two-thirds of drug-induced deaths (64.5% or 1,123 deaths) — a rate of 4.6 per 100,000 population, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. To further underline the safety of cannabis, 6,000 Australians died from alcohol use in 2015, with more than 144,000 hospitalisations between 2012 to 2013, remaining stable at 5.2 deaths per 100,000 or up to and including 2017. Tobacco accounts for more than 15,500 deaths per year. When we compare safety profiles and access, it is ridiculous to consider medicinal cannabis presents any real risk to the public, as it accounts for 0.1 deaths per 100,000 in Australia.

THC Dose-Response

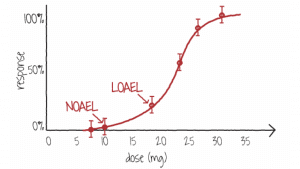

The dose-response relationship correlates exposures with changes in body functions or health. Generally, the higher the dose, the more severe the response. The dose-response relationship is based on observed data from experimental animal, human clinical, or cell studies.

This is where the THC evidence base needs to grow. In most dose-response populations, most responses to a toxicant are similar, with some exceptions in how responses may be encountered. That is, some individuals are susceptible and others resistant. A graph of the individual responses can be depicted as a bell-shaped standard distribution curve. There is a wide variance in responses as demonstrated by the mild reaction in resistant individuals, the typical response in the majority of individuals, and the severe reaction in sensitive individuals.

The results for THC are different. There is a point at which higher doses do not necessarily encounter stronger reactions but simply extend the period of intoxication, and this needs to be conveyed to governments and prescribers alike. The therapeutic effects of a 1:1 CBD:THC ratio may be better than a 1:2 ratio, but there is no increase in adverse effects. Of course, hypothetically, there is a point where a certain potency is reached that may have adverse effects. Apart from the few cannabinoid products that have been subject to more rigorous testing, there is currently not enough information on which to accurately and more precisely predict specific responses.

Additionally, the administrative route is also important as some products such as oils have delayed onset and lose some potency because of first-pass liver enzyme effect, while other products such as vaporisers will work more quickly and have more potency but drop off more quickly than orally ingested dose forms. Realistically, there could be different potencies from different products that may work similarly.

To date, an authoritative dose-response curve does not exist for THC or cannabis in general. Having this data would go a long way to providing the industry support towards establishing its evidence base.

Figure 1 shows a typical dose-response curve where the NOAEL occurs at 10 mg and the LOAEL occurs at 18 mg. This is a sample for information only and not related to cannabis. (https://www.toxmsdt.com/26-noael-and-loael.html).

Figure 1. A dose-response curve showing doses where the NOAEL and LOAEL occur for a substance

(Image Source: NLM)

Looking at uncertainty

The concept of uncertainty looks at the possibility of one individual having a different response to a chemical than another individual. The variables usually used are age, weight and gender, along with time.

A person’s age and body size can affect the clinical and toxic effects of a given dose of many chemicals. Age and body size usually are connected, particularly in children. This relationship is important because a person’s body size can affect the burden that a substance has on it. For example, a typical dose of an analgesic for adults would be toxic to young children. Therefore, many children’s analgesics exist to account for the smaller body size. https://www.toxmsdt.com/21-dose.html.

Another important aspect of uncertainty is the time over which a dose is administered. This makes sense for exposures that occur over several days or that are chronic. However, this uncertainty is based on the possibility that a patient may not follow directions rather than a physical characteristic. This is why therapeutic medicinal cannabis should be prescribed by health practitioners that have an understanding of what product to use and when. Some conditions requiring pain control may need a heavy dose to establish a therapeutic blood level and then smaller doses at specific intervals.

However, uncontrolled dosing would be almost impossible in the case of Novel Foods or in medicinal cannabis and CBPM preparations. Patients will generally limit the dose to the minimum amount to achieve the desired effect due to the cost burden of out-of-pocket medicines or consumer CBD products. For example, in CBD Novel Foods, the effect being sought is associated with the benefits associated with CBD. Any low dose or incidental THC in the preparation may be there as part of an ‘entourage’ effect along with minor cannabinoids, terpenes, flavonoids etc., and as such may flatten the dose curve to allow for smoother symptom management without increasing the risk of intoxication or adverse effects. With medicinal cannabis or CBPMs, the dose of THC is determined by a physician and is script dependent, meaning there are several gate-keepers to prevent chronic over-use, including cost.

What do jurisdictions consider safe?

Australia

The Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) applies a conservative approach to medicinal cannabis products and applies strict controls on the production standards of such products, even those provided under special access schemes. However, it has agreed that higher doses of THC are safe. For instance, it reports:

A single-dose pharmacokinetic study of oral cannabidiol 10 mg, 100 mg and a combination of 10.8 mg THC with 10 mg CBD in healthy volunteers reported that overall, all formulations were considered safe and tolerable. No adverse events were considered serious, and none resulted in withdrawal of a subject from the trial. Headache was the most frequently reported adverse event Therapeutic Goods Administration Safety of low dose cannabidiol (14%– 21%). All adverse events resolved spontaneously without sequel. No clinically significant abnormalities in vital signs, ECG recordings, physical findings or safety laboratory tests were noted. (https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/review-safety-low-dose-cannabidiol.pdf)

The TGA relies upon quality standards to manage risk and is continually upgrading guidance on labelling, consumer medical information, certificates of analysis and advertising to ensure consumers and patients are protected.

Since medicinal cannabis was authorised in 2018, there have been over 200,000 prescriptions written and authorised in Australia for pain alone, most of which contain either low, medium, or high doses of THC without any reported adverse events or deaths. At no stage have the health authorities stepped in to provide warnings or take products off the market. This real data demonstrates a very low risk of use with THC products.

Canada

In Canada, health authorities have been dealing with cannabis derivatives since July 2001, when the government legalised access and production of medicinal cannabis. In October 2018, the Canadian government took the step of legalising adult use cannabis. At present, health authorities have accepted a maximum dose of 10mg THC, however, most doctors recommend a dose somewhere between 2.5 and 5 mg of THC for medicinal cannabis patients.

There were almost 300,000 medicinal cannabis patients in Canada in March 2021 who have had at least one prescription. Better labelling and education around cannabis products and their use has resulted in more informed choices by consumers but not led to increased usage, with medicinal cannabis rates remaining stable over the last two years, despite the pandemic.

Quality guidelines for adult use Cannabis align with food standards rather than the pharmaceutical standards outlined in Australia; despite this, there has been no rise in adverse reactions amongst adults. Any increase in adverse reactions amongst children has been due to high dose THC exposure and the lack of child-proof containers for such high THC products.

THC exposure in CBD Novel Foods in the UK is limited to 1mg per container by the MDA 1971 and MDA 2001, mitigating against any accidental exposure risk to children. Container size is an important element that should be examined in more detail, particularly in the UK, where different labelling methods could provide more uncertainty for consumers.

There exist large volumes of data from jurisdictions such as Australia and Canada, which, if accessible, could be used by academia to analyse and provide valuable insights that could provide more certainty around the effects of THC.

The lack of certainty of key stakeholders, like government and clinicians, about the effects of THC that are holding back progress in the medicinal cannabis and consumer CBD sectors in many jurisdictions, is, in large, due to a lack of education. Regulators and the medical profession need access to statistical information about the low-risk profile of THC compared to other substances, showing that there is more certainty about the effects of THC than they currently accept. Without this, there will continue to be some distrust in its use. Meta-analyses of the large amount of special access data being gathered by regulators around the world would go a long way to bridging this gap.

The parameters that need to be addressed to advance confidence and understanding of THC are:

- The nature and severity of the effect of THC at different doses;

- The differences in exposure (administration route, duration, frequency and pattern) of THC;

- The dose-response relationship observed; and

- The overall confidence in the evidence database.

As previously mentioned, some jurisdictions have allowed medicinal cannabis products with THC to be prescribed for many years. Such a wealth of data of prescribing exists side-by-side with the same number of years with safe use and little to no adverse events. More research can be done to supplement what we have already, provided jurisdictions allow transparent use of such data. A comprehensive evidence base for the effects of THC will benefit everybody, regulators, physicians, producers and most importantly, patients and consumers.

References

- Arnold, J.C. 2021. Australian Journal of Clinical Practice. A primer on medicinal cannabis safety and potential adverse effects. Vol 50, Issue 6.

- Arnold, J.C et al. 2020. Australian Prescriber. Prescribing Medicinal Cannabis.

- Health Canada releases new data on cannabis use in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2021/12/health-canada-releases-new-data-on-cannabis-use-in-canada.html